History of the Cathedral

Westminster Cathedral is relatively ‘modern’ in historical terms. Building only began in 1895 and the Cathedral was completed just eight years later in 1903 but its unique architecture reflects the influences of ancient Christian churches and its construction marks a pivotal moment in the history of the Church in England and Wales.

Rejection of a Gothic vision

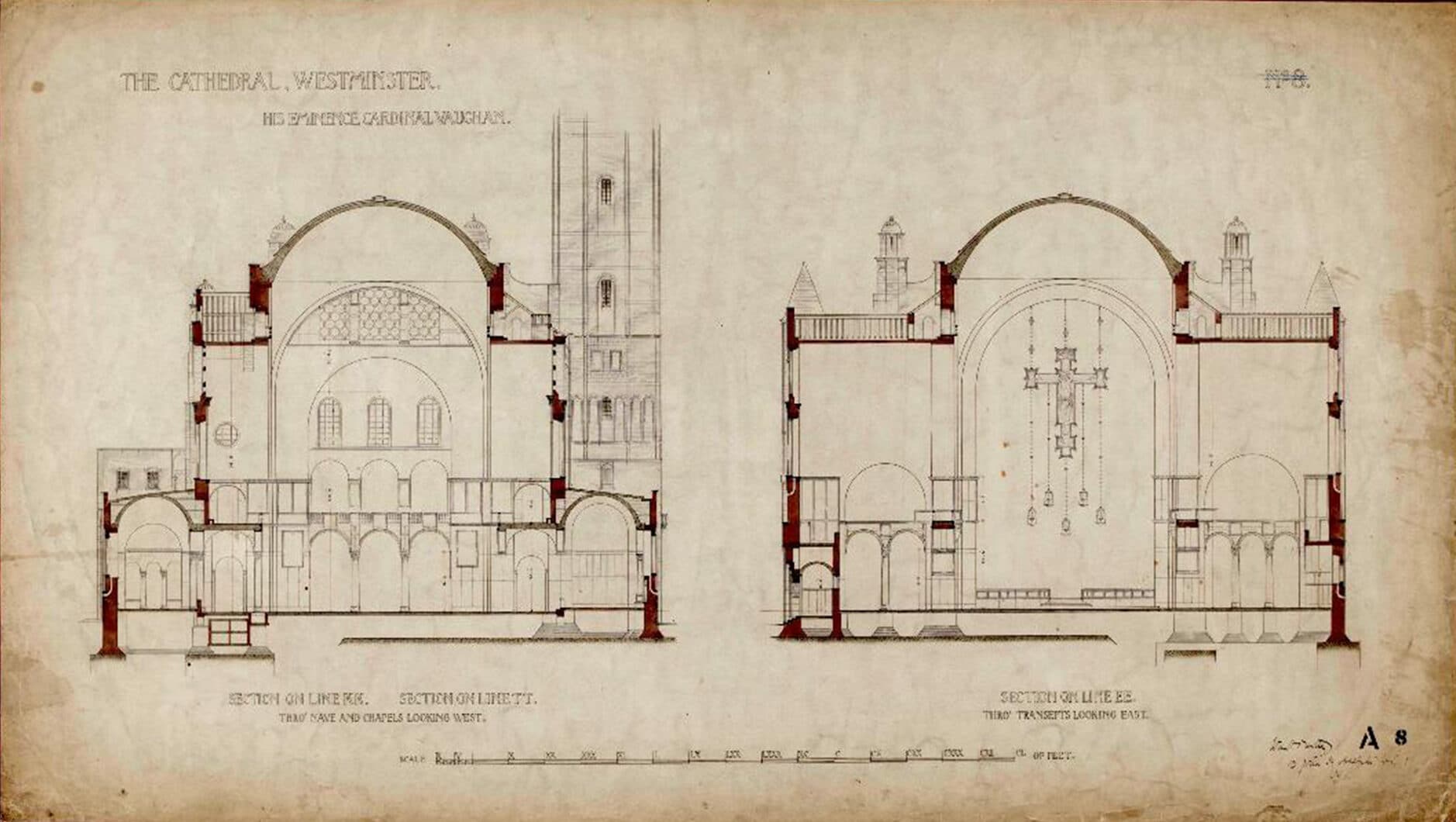

On his appointment to Westminster, Cardinal Vaughan promised that a Cathedral would be built within ten years, but he was pragmatic. The diocese urgently needed a Cathedral – a statement of religious authority and the seat of the Archbishop’s ‘Cathedra’ – but it did not have unlimited funds. The new cathedral for Westminster would ultimately reflect many of the grand buildings of the industrial age; the mills and factories in brick which dominated the working landscape of Victorian Britain. Brick was significantly cheaper than stone, and readily available as a building material.

Vaughan had three key requirements for his new church: first, a broad uninterrupted nave with the high altar as the focus; second, a building whose structure could be completed first (the decoration could come later) and third, sensitive to the politics of the age, a desire not to compete with the Gothic grandeur of Westminster Abbey, a near neighbour. The Cardinal wanted a new vision for the new diocese, not a poor replica of the past.

An exciting new Cathedral for a new age

Cardinal Vaughan was familiar with the grand basilicas of Rome and he was convinced that an early Christian style church ‘of the Italian type’ was suitable for Westminster. In the late 19th century, Catholicism in England was enjoying a resurgence, boosted by an immigrant Irish population fleeing from famine and poverty, and the churches attracted large congregations. Vaughan rejected a narrow Gothic-style design in favour of a large interior space that referenced the ancient history of the Church.

‘We want the Empire to possess, in its very centre, a living example of the beauty of the majesty of the Worship of God, rendered by solemn daily choral service.’

Cardinal Herbert Vaughan

The Building Fund

‘Cardinal Vaughan wanted ‘to put Catholicism back on the map…to inspire and encourage his flock after centuries of being forced into the shadows’. Feargal Martin, Gen. Sec. Catholic Truth Society

Cardinal Vaughan was a tireless fundraiser whose efforts had led to the establishment of a missionary training college at Mill Hill in North London. He set about the task of paying for the Cathedral building works with the same vigour and called on the protection of St Joseph for the fundraising effort. He said: ‘The work of finding the means, has been placed under the fostering care of that great Patriarch.’

Writing to a priest in 1897, the Cardinal argued that ‘to pay off debt seems to be a thankless labour…but in reality, such work deserves the highest praise’.

Vaughan chose to finance the work by establishing a Founders scheme; individuals were asked to pledge £1000 or more to the Building Fund (a pledge worth £11,000 today). Early major donors included the Duke of Norfolk, Fr Hugh Benson (brother of Mapp and Lucia author EH Benson) and the writers GK Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc. The Duchess of Norfolk gifted a large 55cwt bell for St Edward’s tower and parishes across the country were petitioned for funds. Individual communities undertook to pay for aspects of the work. A Miss Willis, appealed to the former pupils of the Sacred Heart Convents to help fund the completion of the Sacred Heart Chapel.

Under Canon Law a Cathedral cannot be consecrated whilst debt remains. Cardinal Vaughan’s death in 1903 meant that the fundraising impetus slowed and the task of paying for the Cathedral building work fell to his successor Cardinal Francis Bourne. In March 1910, the Westminster Cathedral Chronicle reported that £7000 of debt remained and Cardinal Bourne appealed again for donations. There is, he said, yet ample opportunity for ‘generous co-operation in the great work’.

The fundraising target was finally reached on the evening of Saturday 30 April 1910. The Cathedral was free from ‘any debt upon its structure’ and plans for the formal ceremony of consecration could proceed. Bourne, the fourth Archbishop of Westminster, praised the ‘united generosity of Catholics of every position and degree scattered the world over’.

Consecration

The timetable of ceremonies extended over three days from June 27 to June 29, the great feast of SS Peter and Paul. The Westminster Chronicle said it was, ‘an epoch in the history of the Catholic Church in England’.

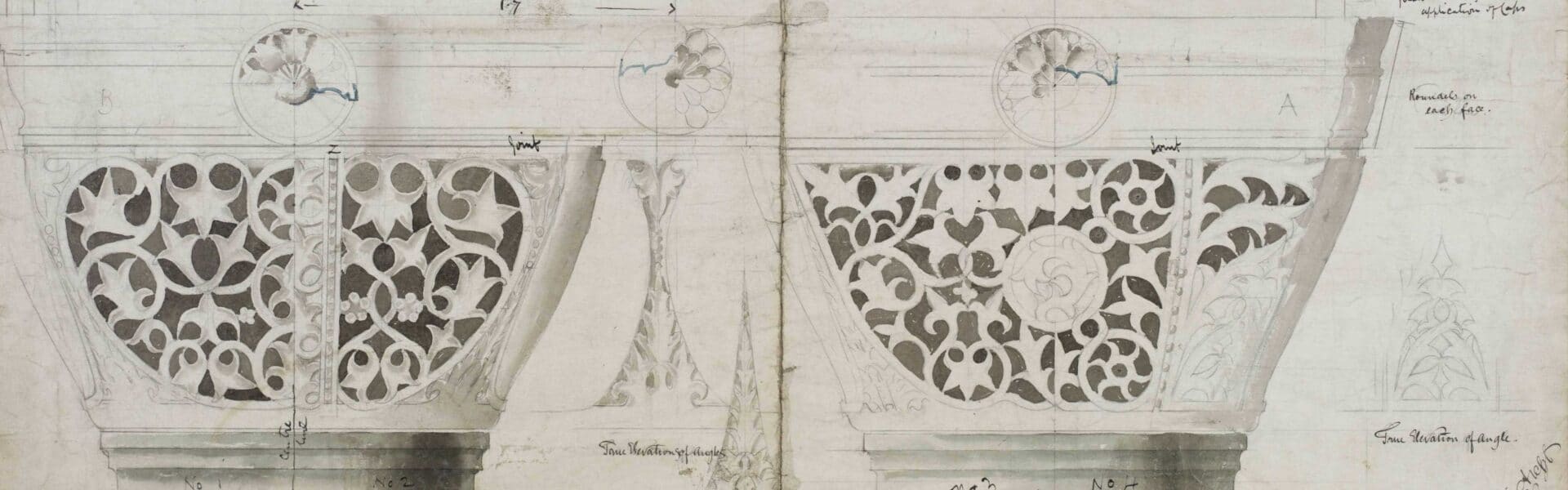

The ceremonies began on 27 June with Exposition of the Relics in the Cathedral Hall and these were then sealed in silver caskets – one each for the 13 altars of the Cathedral. On the 28th the altars were consecrated, the silver caskets inserted into each altar in turn with Osmond Bentley, the architect’s elder son, assigned the task of sealing in the casket for the High Altar. A formal Mass of Dedication was sung by the Rt Rev John Baptist Cahill, Bishop of Portsmouth. Vespers and a Te Deum sung during Benediction marked the formal thanksgiving for the consecration of the Cathedral and the restoration of the Hierarchy. The ceremonies concluded on the Feast of SS Peter and Paul with a Mass sung by Archbishop Bourne and attended by the Lord Mayor of London; Vespers and Benediction at 4pm, followed by Compline, concluded the proceedings and a grand dinner was held at the Mansion House in the evening to mark the occasion and celebrate the achievement. Only 15 years previously the site ‘now covered by that stately monument of Catholic revival’ was a field.

Bentley’s name is not recorded in the Cathedral. In common with Christopher Wren, the building alone is his monument.