Over a century’s-worth of mosaics

Mosaics have always been an integral part of Westminster Cathedral and designs range from the traditional arts and crafts style to more modern interpretations.

Part I - Trial and Error

When the Cathedral architect, John Bentley, died in early March 1902, he left no finished mosaics in the Cathedral and very little in the way of Mosaic drawings and designs. It was thus left to future architects, donors and designers supervised, from 1936, by the Cathedral Art Committee, to decide on the mosaics.

Bentley’s 1895-96 drawings of the west and north elevations include small pencil sketches of mosaics above both the main and north-west entrances, and in 1899 he provided a written outline for the decoration of the Lady Chapel and one of the chapels of the north aisle. But the only one of these schemes to be adopted was that above the main entrance which was put in place, with some alterations, in 1915-16.

Cardinal Vaughan, the Cathedral’s founder, had also been considering the question of the mosaics, and between 1899 and 1901 a total of twelve prominent Catholics, half of them clerics and half laymen, had been asked to provide written suggestions for a scheme for the nave. Vaughan had expressed the view that this should tell the history of the Catholic Church in England and most of the responses consisted of lists of scenes and saints illustrating this theme. But Bentley’s death, followed by that of the Cardinal in June 1903, put an end to the initiative.

Bentley’s ideas can best be seen in the Chapel of the Holy Souls where he worked with the artist, W C Symons, on the mosaics. Symons was an old friend and fellow convert, and in 1899 Bentley had asked the Cardinal that he should decorate one of the chapels (with Bentley himself doing another). Correspondence between him and Symons in 1900 on the themes for the mosaics of the Holy Souls Chapel reveals that Symons suggested the Three Youths in the Burning Fiery Furnace for the west wall, while Bentley suggested the Purgatory scene with the archangels Raphael and Michael for the east wall. Symons also suggested portraying Adam and Eve though Eve was later rejected in favour of Christ for the north wall.

Bentley’s influence in the Holy Souls is evident. He wanted ‘a severe and very Greek style’ and supervised the sketches and subsequent full-size cartoon in Symons’ studio, designing two garlands for the vault himself. To install the mosaics, they chose George Bridge and his twenty-six young lady mosaicists of Mitcham Park, Surrey, who had an Oxford Street studio to which Bentley was a frequent visitor. Initially it was intended to prepare much of the mosaic face downward on canvas in the studio (the indirect method). But this was not a success and was soon abandoned. Instead the direct method was adopted in which the glass tesserae, largely made by Bridge himself, were inserted individually directly into the putty (of lime and boiled oil) on the walls and vault.

Installation of the Holy Souls mosaics took eighteen months, from June 1902 to November 1903. The opus sectile glass tiles for the altarpiece were made by George Farmiloe & Sons and they and the Great Rood (crucifix) in the nave were painted by Symons also in 1903. But with a wife and nine children he wanted the work to continue. Advised in a letter of April 1903 from George Bridge (who also wanted work) that a rival, the Venice and Murano Glass Company, had bid to execute the mosaic above the main entrance, Symons submitted his own design for this to the Cardinal in May. But Vaughan died in June. So, urged on by Revd Herbert Lucas SJ, one of the twelve who had put forward a general scheme for the nave, Symons approached Vaughan’s successor, Francis Bourne, seeking an interview to discuss his mosaic designs for both the entrance and the Blessed Sacrament Chapel.

But Bourne was not to be rushed and seems to have resented the pressure. Nor would he agree to Symons’ request in 1904 to be allowed to work on one of the chapels as a model. The only commissions Symons received were to design mosaic panels of St Edmund in the crypt, St Joan of Arc in the north transept and the Holy Face in the Shrine of the Sacred Heart, all executed by George Bridge and his mosaicists using the direct method in 1910-12. Symons’ design for the Holy Face was death mask, disliked by the donor, but he refused to change it. He died in 1911 and in 1916 the Sacred Heart Shrine mosaics, all executed by Bridge, were taken down and replaced by James Powell & Sons of Whitefriars at a cost of £780, the new Holy Face being based on one in St Mary’s Cadogan Terrace, Chelsea.

Part 2 - Opus Sectile and the Italian Method

The decoration in the Chapel of St Gregory and St Augustine was installed at the same time, and by the same group of mosaicists, as that in the Holy Souls Chapel across the nave. But despite this it is in complete contrast – the result of having a very different donor, designer, technique and style.

Lord Brampton, the donor, was a distinguished judge and a friend of Cardinal Manning, the second Archbishop of Westminster. He joined the Catholic Church in 1898 and paid £8,500 (£300,000 today) for the decoration of St Gregory and St Augustine’s, which was intended to be both a thanksgiving offering and a chantry chapel for his wife and himself. The theme is the conversion of England from Rome, with the saints who brought this about portrayed in opus sectile above the altar, and those who subsequently kept the faith alive in this country shown in mosaics on the walls and vault.

Lord Brampton selected Clayton & Bell of Regent Street, renowned for its ecclesiastical stained glass, to design the decoration. For the altarpiece showing St Gregory, St Augustine, his companions and successors, J R Clayton, the firm’s head, chose opus sectile from James Powell & Sons, Glassmakers of Whitefriars. In the 1860s Powells had started grinding up waste glass and baking it, to produce panels of opaque material with an eggshell finish which could be cut into suitable shapes and painted. These glass tiles they named opus sectile. Those forming the altarpiece were made in 1901 from Clayton & Bell’s drawings. The panels either side of the entrance are later: ‘the Just Judge’ – Clayton & Bell’s memorial to Lord Brampton, who died in 1907, and ‘Not Angles but Angels’ – given by the Choir School in 1912.

J R Clayton believed that any attempt to revive the dead in art was a profound mistake and he ignored the wishes of the Cathedral Architect, J F Bentley, that the Byzantine (Greek) style should be adopted. Instead his designs were similar to those he produced for Victorian Gothic churches. Full-size coloured drawings for the mosaics were sent over to the Venice and Murano Glass company in Venice where, using a technique invented there in the mid-19th Century, the regular, rectangular, coloured glass tesserae were attached to the drawings face down before being dispatched to England. From December 1902 to May 1904, George Bridge’s mosaicists, already working in the Holy Souls Chapel, hammered each section into place with mallets and flat pieces of boxwood, before removing the drawings to reveal the mosaics, now face up, below.

In the Holy Souls Chapel opposite, Bentley and Symons seem to have been given pretty much a free hand by the donors, the Walmsleys, in choosing the designs. Though it must be said that the result is more Victorian (Art Nouveau in the case of the representation of Adam) than the Byzantine for which Bentley was striving. After an unsuccessful attempt at prefabrication in the studio, installation of the mosaics was by the traditional, direct method and the tesserae were inserted individually into oil-based putty on the chapel walls and vault. George Bridge had installed the mosaics for the façade of the Horniman Museum in London in 1900-01, using tesserae he had largely made himself.

The Chapel of St Gregory and St Augustine is in complete contrast to that of the Holy Souls. Judge Brampton knew exactly what he wanted and chose Clayton & Bell to carry it out. J R Clayton disregarded Bentley’s instructions to avoid anything Gothic and used the style he normally used. James Powell & Sons had invented the modern technique of opus sectile and were expert at it. The Venice & Murano Glass Company was equally accomplished at producing mosaics and Antonio Salviati, its previous head, claimed to have invented the ‘modern Italian method’ in which they were prepared face downwards in the studio – the method employed here.

The Holy Souls Chapel mosaics are sombre, funereal, late Victorian pictorial on a background of silver. Those of the Chapel of St Gregory and St Augustine are glowing, vibrant, late Victorian Gothic on gold. Both are impressive in their own way, but they have little in common.

Part 3 - The Arts and Crafts Men

The decoration of the Cathedral in the period 1912-16 was largely the work of members of the Arts and Crafts Movement, notably Robert Anning Bell and Robert Weir Schultz. Eric Gill was also associated with the Movement, though he had distanced himself by the time he produced the Stations of the Cross. Their work is among the best in the Cathedral.

The Arts and Crafts Movement, originating in mid-19th century Britain with the ideas of John Ruskin, believed that industrialisation and mechanisation dehumanised those involved and debased craftsmanship. The Movement advocated individualism and creativity in art and design and a return to traditional materials and working methods. Robert Anning Bell RA was experienced in art and architecture and a designer of stained glass, mosaics, fabrics and wallpaper. In 1900-01 he had produced a 32ft by 10ft mosaic for the façade of the Horniman Museum in London. He was Professor of Decorative Art at the Glasgow School of Art when John Marshall, the Westminster Cathedral architect and a fellow Nonconformist, approached him.

The walls of the Lady Chapel in the Cathedral had been clad with marble in 1908, but although a carved white marble frame had been put up above the altar, it was empty of any altarpiece and the conches above the four marble-clad wall niches were also undecorated. At Marshall’s request, Anning Bell produced a mosaic design for the altarpiece portraying Our Lady standing and holding the Holy Child. For the conches he portrayed Isaiah, Jeremiah, Daniel and Ezechiel, all Old Testament prophets who had foreseen the Incarnation. The predominantly blue mosaics were installed in 1912-13, under the supervision of Anning Bell and Marshall. The traditional, direct method was employed by the experienced mosaicist, Gertrude Martin, who had worked for George Bridge on the mosaics of the Holy Souls Chapel ten years earlier.

The mosaics were generally praised and, although Cardinal Bourne himself was disappointed, he agreed that Anning Bell should design the mosaic over the main entrance. Bentley had provided a small sketch in pencil for this in 1895-96 and Marshall had worked this up in colour in 1907. These sketches were very largely followed by Anning Bell but the open book with the words (in Latin) “I am the gate, if anyone enters by Me he shall be saved” is a new theme, and the mosaic is considerably simpler and more austere, with more subdued colours, than in the earlier designs. It is clear that Anning Bell devoted considerable thought to it, rejecting gold as liable to frost damage and bright colours as too great a contrast with the background. The mosaic, grouted up to a level surface, was installed in 1915-16 by James Powell & Sons of Whitefriars, who also replaced the mosaics in the Sacred Heart Shrine at this time.

Meanwhile other members of the Arts and Crafts Movement were at work in St Andrew’s Chapel. Robert Weir Schultz (Schultz Weir from 1915) was architect to the 4th Marquess of Bute, who had sent him to study Byzantine architecture in Greece. The Marquess had offered to pay for the decoration of St Andrew’s Chapel providing that Schultz designed and supervised this. The mosaics on the far wall portray cities connected with St Andrew’s life – a fisherman born in Bethsaida, later Bishop of Constantinople, finally crucified in Patras in Greece. The near wall follows the journey of his relics, after being seized in Constantinople in 1204 by the 4th Crusaders, to Milan, Amalfi and, of course, St Andrews in Scotland. The floor is a stormy sea inset with twenty-nine marine creatures while the altar consists of three Scottish granites.

Besides Schultz himself, other Arts and Crafts colleagues who worked on the Chapel were: George Jack (the mosaic cartoons), Thomas Stirling Lee (sculpture), Ernest Gimson (inlaid ebony stalls) and Sidney Barnsley (kneelers). Schultz’s designs were approved in 1910 and the mosaics installed in 1914-15 by six of Ernest Debenham’s group of mosaicists directed by Gaetano Meo, using tesserae from both Venice and Powell & Sons (red and gold). These were inserted by the traditional, direct, method into cement of the same composition as used by Sir William Richmond in St Paul’s Cathedral. The mosaics are outstanding examples of quality and craftsmanship, particularly the shimmering fish-scales (or ‘golden clouds screening Paradise from earthly view’) on the vault, and the arches where thirty-three birds perch amidst the foliage.

Part 4 - The Impossible Dream

More mosaics went up in the Cathedral between 1930 and 1935 than at any time before or since. Yet their style resulted in the greatest public furore witnessed in the Cathedral’s history. For the origins of the situation we have to go back almost to the beginning of the century.

When Francis Bourne succeeded Herbert Vaughan as Archbishop of Westminster in 1903, the only mosaics in place were those designed by W C Symons in the Holy Souls Chapel and those opposite in the Chapel of St Gregory and St Augustine, designed by J R Clayton of the firm of Clayton and Bell. Bourne was happy with neither. In November 1905 he was in Rome and from there travelled to Sicily specifically to see the 12th century Byzantine mosaics in Palermo’s Palatine Chapel and in the great Cathedral of Monreale nearby. There at last Bourne found what he wanted, speaking on his return of his intention to reproduce the mosaics in Westminster Cathedral.

Almost twenty years went by but Cardinal Bourne was satisfied with none of the Cathedral mosaics. To commemorate his twenty years as Archbishop of Westminster, Bourne had his portrait painted in 1923. The artist was Gilbert Pownall, a Catholic who had exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy from 1908. Bourne believed that at last he had found the right man to design the Cathedral mosaics. As Pownall had little or no experience in this medium, Bourne arranged for him to go to Ravenna, Rome, Venice and, of course, Palermo and Monreale, to study the masterpieces in mosaic there as Bourne himself had done. On his return, Bourne asked him to design mosaics first for the alcove above one of the main confessionals and then for the Lady Chapel. He also announced that a mosaic workshop would be set up in the tower. The designs were accepted and in 1930 the workshop was established with Basil Carey-Elwes and T Josey as the first mosaicists.

The confessional mosaics were completed in the same year (1930), using the direct method, and a start was then made on the Lady Chapel. By now the team of mosaicists had grown, to three and then to five with the arrival of two experienced Italians in 1931. The Lady Chapel mosaics took five years, being completed in June 1935. Meanwhile the blue sanctuary arch mosaic was put up by the Italians in 1932-33, St Peter’s Crypt received its mosaic in 1934 and work started on the Cathedral apse in the autumn of 1934. But from December 1933, Edward Hutton, an expert on Italian art, had started to organise leading figures in the art world in a protest against Gilbert Pownall’s style, which Hutton regarded as ‘amateurish, clumsy and without mastery’. When Bourne died in January 1935 his successor, Arthur Hinsley, gave in. The partially completed apse mosaic was taken down and only the war saved the sanctuary arch.

So how much of Bourne’s dream of bringing Monreale to Westminster was achieved? The main theme of the Lady Chapel – the Tree of Life and the vine – are clearly taken from the 12th century apse of San Clemente in Rome and many of the animals, including the unusual fish-like creatures at the termination of tendrils, are the same. The mandorla of Christ on a rainbow in the Lady Chapel apse appears to be from the Ascension dome in St Mark’s Venice, while the blue entrance arch of the chapel may derive from the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna. We know from Bourne that the Cathedral sanctuary arch mosaic of Christ enthroned among evangelists and apostles was inspired by the 4th century apse of Santa Pudenziana in Rome, though the treatment is vastly different. Only the engagingly simple yet effective arch of St Peter in the crypt and perhaps also the confessional mosaics, have any real affinity with the mosaics of Palermo and Monreale. But then dreams often are impossible.

Part 5 - A Russian Perspective

The furore over the new Cathedral mosaics in 1934-35, followed by the War, resulted in no new mosaics until 1950. The subsequent period was dominated by the Russian, Boris Anrep.

The very public row over Gilbert Pownall’s mosaics for the Lady Chapel, the sanctuary arch and the apse led to Cardinal Hinsley ordering the removal of the latter and setting up a committee to advise him on decoration. This lapsed with Hinsley’s death in 1943 and his successor, Cardinal Griffin, himself authorised two new mosaics – one representing St Thérèse of Lisieux in the south transept (designed by John Trinick and installed in 1950) and the other of ‘Christ the Divine Physician’, a memorial to the officers and men of the Royal Army Medical Corps, designed and installed by Michael Leigh in St George’s Chapel in 1952.

These and other decisions resulted in a letter of protest to ‘The Times’ in late 1953, signed by many of those who had protested to Hinsley about Pownall’s designs and criticising recent mosaic work as ‘conspicuously lacking in the fine qualities of the art’. Cardinal Griffin hurriedly reconstituted the advisory committee. In 1958 the mosaic of St Thérèse of Lisieux was replaced with a bronze by Giacomo Manzu. Before this, in 1954, the committee had asked Boris Anrep to design a new sanctuary arch mosaic but his estimate was too high. A Russian by birth, Anrep had been responsible for the mosaic on the vault of the inner crypt in 1914. But this was interrupted by the War when he returned to Russia to lead his troop of Cossacks, rescuing church icons in the process. After the Russian Revolution he returned to England. In 1924 he produced using the indirect method as he always did, the mosaic of St Oliver Plunket outside St Patrick’s Chapel, and in 1937 he designed mosaics for this chapel but they were judged too costly.

Anrep was now offered the Blessed Sacrament Chapel and in 1956 he produced a model with three main themes illustrated by scenes from the Old Testament (in the chapel nave) and from the New (in the apse). The first is Sacrifice – on the left Abel, then Abraham, Malachi and Samuel; on the right Noah. Interwoven with this theme is that of the Eucharist with the Hospitality of Abraham, the Gathering of Manna, Abraham and Melchisadek and an angel persuading Elijah to eat, continuing with ears of wheat and grape vines in the window arches into the apse with the Wedding Feast at Cana and the Feeding of the Five Thousand. The third theme is the Trinity – Abraham’s guests again, the three youths in the fiery furnace and the Trinity itself high in the apse.

Anrep chose a traditional, early Christian, style and a predominantly pale pink background to give a sense of light and space and to blend in with the marbles. Together with his assistant, Justin Vulliamy, and using the indirect method, Anrep then produced full-size coloured cartoons of the designs in his Paris studio and sent these to Venice where tesserae from Angelo Orsoni’s workshop were attached and the results crated and sent to London. The installation of the mosaics took place from 1960-62, with Peter Indri doing the fixing and Anrep himself, wreathed in smoke from his habitual Gauloises, making constant adjustments on a huge work table partitioned off in the north transept.

Meanwhile, Aelred Bartlett, brother of the Cathedral Sub-Administrator, had produced the vine and star mosaics in the transept arches and the Roman-style representation of St Nicholas in the north aisle in 1961. But for St Paul’s Chapel the committee turned again to Anrep, now almost eighty. He provided a scheme in 1961 but arranged that his assistant, Justin Vulliamy, fresh from producing a mosaic of St Christopher in the north aisle, take over. Using the indirect method again, the mosaics, showing St Paul’s conversion, shipwreck off Malta, place of execution and occupation as tent-maker (the tent on the vault), were prepared in Paris and Venice in 1962-63 and installed by Peter Indri in 1964-65. Anrep acted as adviser and detailed the principal figures but disliked the final result and distanced himself from it. He died in 1969 aged eighty-five.

Part 6 - The Journey proceeds

After all the activity in the early 1960s, there was a prolonged lull in the Cathedral decoration which really only came to an end as the millennium itself drew to a close.

There were three reasons for the absence of activity. Cardinal Heenan had succeeded as Archbishop of Westminster in 1963, and although he allowed the work underway to continue, he believed that there things should end. In the words of his new Administrator in 1964 “it is time to turn our minds to the plight of men and women in undeveloped countries”. Secondly the Second Vatican Council was underway, one of its aims being to concentrate on essentials. Thirdly there was no money.

So it was that no new mosaics went up until 1982 when, to commemorate the visit of Pope John Paul II that year, a mosaic designed by Nicolete Gray was installed over the unused north-west entrance from Ambrosden Avenue. In 1895 John Bentley, the Cathedral Architect, had produced a pencilled sketch for a mosaic here, showing Our Lady and the Christ child seated with a saint on either side. This was now ignored in favour of the inscription ‘Porta sis ostium pacificum par eum qui se ostium appellavit, Jesus Christum’ (May this door be the gate of peace through him who called himself the gate, Jesus Christ).

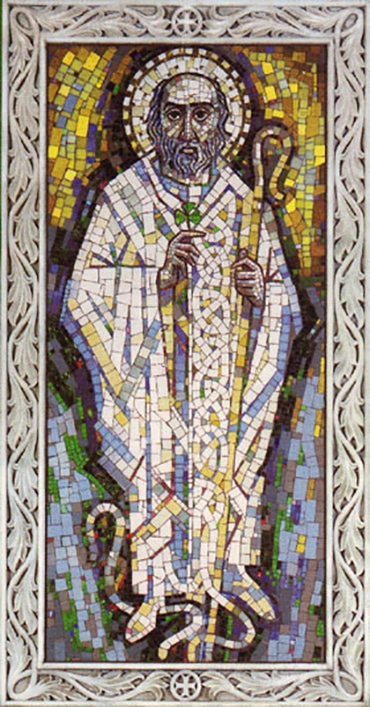

Nicolete Gray was an epigrapher, a maker of designs with capital letters. She also designed the memorial of the Pope’s 1982 visit in front of the main sanctuary and the inscription on Cardinal Heenan’s tomb (1976) in the south aisle, but her design for the north-west entrance was her first in mosaic. It was executed by the mosaicist Trevor Caley. Fifteen years later he returned to the Cathedral for its next mosaic at the entrance to St Patrick’s Chapel. Caley initially envisaged an interpretation of the 7th century stone cross at Carndonagh in Donegal but this was changed to one of St Patrick shown holding a shamrock and crozier with a writhing snake beneath. Using a mixture of unglazed ceramic material and glittering glass tesserae from Cathedral stocks, Caley produced the mosaic on board in the studio and installed it in March 1999.

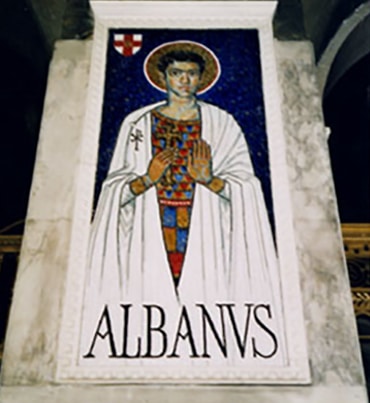

The next mosaic appeared on the opposite side of the nave two years later. It was of St Alban, the Romano-British soldier executed for his faith. Designed by Christopher Hobbs, it was assembled by Tessa Hunkin in the Hackney studio of Mosaic Workshop using the indirect method and installed in the Cathedral by her and Walter Bernadin in June 2001, in cement composed of ceramic tile adhesive with an additive to increase adhesion and flexibility. The striking representation of St Alban is heavily influenced by early Byzantine iconography, the saint carries a cross as a demonstration of his faith and his other hand is raised in blessing. The red line around his neck symbolises decapitation.

The next project was the completion of St Joseph’s Chapel with mosaics, a costly undertaking requiring £300,000. After his success with St Alban, Christopher Hobbs was again chosen as the designer. In 2002 his representation of the Holy Family, clearly also drawing on the Byzantine, was projected onto the apse of the chapel with an overhead projector, and outlines traced onto the surface. The mosaic was made and installed by Mosaic Workshop in 2003, once again using the indirect method. Hobb’s designs for the west wall show craftsmen building the Cathedral, while the vault has been decorated with a multi-coloured basket-weave pattern. Installation was completed in 2006

Meanwhile the Friends of the Cathedral, including those in America, have raised the £200,000 for the mosaics in the Chapel of St Thomas Becket (the Vaughan Chantry). Christopher Hobb’s designs for the east wall show St Thomas standing in front of the old Canterbury Cathedral and those for the west show his martyrdom, with a delightful pattern of tendrils, flowers and roundels against a deep blue background for the vault above.

The designs are a masterly combination of medieval English scenes with the Byzantine style. Installation by Mosaic Workshop took place in 2004. There are also plans for St George’s Chapel and mosaics of St Francis and St Anthony in the narthex, while discussions continue regarding St Patrick’s Chapel and the Baptistery.

Part 7 - The Mystery Mosaics

In the February 2005 edition of Oremus we asked for help in discovering the origins of the niche mosaics of St Anne and St Joachim at the end of the south aisle. Many thanks to those who responded. Canon Arrowsmith remembers that they were produced in the 1960s, he thought by Aelred Bartlett. Paul Bentley, however, tells us that Aelred Bartlett had told him that they, together with the niche mosaic of St Christopher across the nave in the north aisle, had been produced by Justin Vulliamy. The mosaic of St Joachim is also linked to that of St Christopher in that both refer in their dedication to members of the Hoffman family.

Aelred Bartlett was the brother of Canon Francis Bartlett, the Cathedral Sub-Administrator at the time, and is on record as producing the mosaic of St Nicholas, the first of the aisle niche mosaics to be produced, in the north aisle in 1961. He was particularly proud of this mosaic, which was influenced by the 4th century nave mosaics in the Basilica of St Mary Major in Rome, and is very different in character from the other niche mosaics here in the Cathedral. At this time (the early 1960s) Justin Vulliamy was working as artistic and technical assistant to Boris Anrep, with whom he had worked from the 1930s. In 1956 Anrep had been commissioned to produce mosaics for the Cathedral Blessed Sacrament Chapel, these being finally completed in January 1962 when the chapel was reopened.

The previous year (1961) Anrep had produced designs for the mosaics of St Paul’s Chapel for the Cathedral Art Committee but, by now aged almost 80, he asked that Vulliamy, his assistant, should be given the commission to design and decorate the chapel while he himself would advise and assist him. Vulliamy is recorded as working on the mosaics of St Paul’s in Paris (where Anrep had his studio) and Venice (where the firm of Angelo Orsoni made the glass smalti and tesserae and prepared the mosaics) from 1962 until 1964. During that year the mosaics were installed (by Peter Indri) in the chapel which was reopened in January 1965.

Thus Vulliamy is known to have been working on Cathedral mosaics from 1962-64 and so was in a position to have produced the three niche mosaics of St Christopher, St Joachim and St Anne, as remembered by Aelred Bartlett. In support of this is the use in all three niche mosaics of the same unusual violet-pink smalti as used in the Blessed Sacrament Chapel and St Paul’s. Also used in these two chapels and in the mosaics of St Anne and St Joachim – but nowhere else in the Cathedral – are granulated gold tesserae interspersed with the normal flat-faced type. The same violet-pink smalti and granulated gold tesserae were produced by Angelo Orsoni of Venice – the firm which supplied Anrep and Vulliamy.

Anrep himself is, of course, very unlikely to have been involved with the three niche mosaics, having turned down the commission for St Paul’s Chapel because of age. In any case his style is completely different – as can be seen by comparison with his mosaics in the Blessed Sacrament Chapel and with the principal figures (which he detailed) in St Paul’s. So it looks as if Aelred Bartlett was right in that the niche mosaics were produced by Justin Vulliamy in the period 1961-64 (after which decoration effectively came to a halt under Cardinal Heenan and his new Administrator) using smalti and tesserae produced by Orsoni of Venice with Peter Indri again doing the fixing – as he did in the Blessed Sacrament Chapel and St Paul’s.