Bentley’s Vision

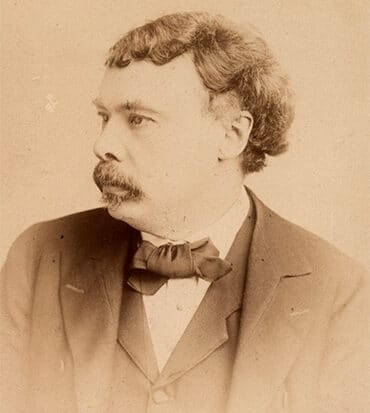

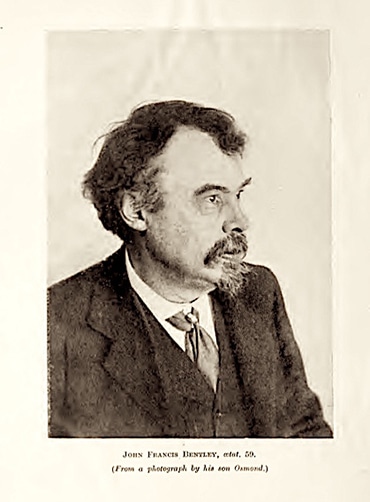

Cardinal Vaughan needed an exceptional architect to make his vision a reality. A new cathedral for the Catholic Church in England and Wales was a prestigious commission and, as news spread, young architects lobbied to be put forward for the expected architectural competition. But Cardinal Vaughan on advice declined a competition and appointed the ‘best’ Catholic architect in England: John Francis Bentley.

The Grand Tour

Bentley’s architectural designs up to 1894 were very much of their time: neo-Gothic Victorian. There was nothing in his portfolio that hinted at the Byzantine except a beautiful monstrance that he had created for the church of St Francis, Notting Hill. In November 1894, with Cardinal Vaughan’s exacting brief in his pocket, Bentley set off for Italy in search of architectural inspiration. His first stop was the northern city of Milan and the Church of S. Ambrogio with its impressive baldacchino and then on to Pavia, Pisa, Naples and Rome.

Bentley was unimpressed with the Holy City, disliking the style and scale of St Peter’s baroque basilica and he also rejected the rebuilt basilica of St Paul’s outside the walls which was in Vaughan’s preferred Early Christian style.

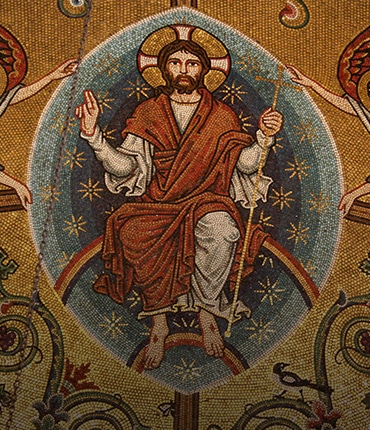

From Rome he went to Ravenna, to see the architecture and mosaics of San Vitale, and then on to Venice and St Marco. An outbreak of cholera in the city prevented him from visiting Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (Istanbul). He declared that WR Lethaby and Harold Swainson’s: The Church of Sancta Sophia, Constantinople: A Study in Byzantine Building, which had been published in 1894, told him all he needed to know. He returned home via Paris, arriving back in London in March 1895.

‘Beyond all doubt the finest church

that has been built for centuries.’

Richard Norman Shaw

Byzantine Revival

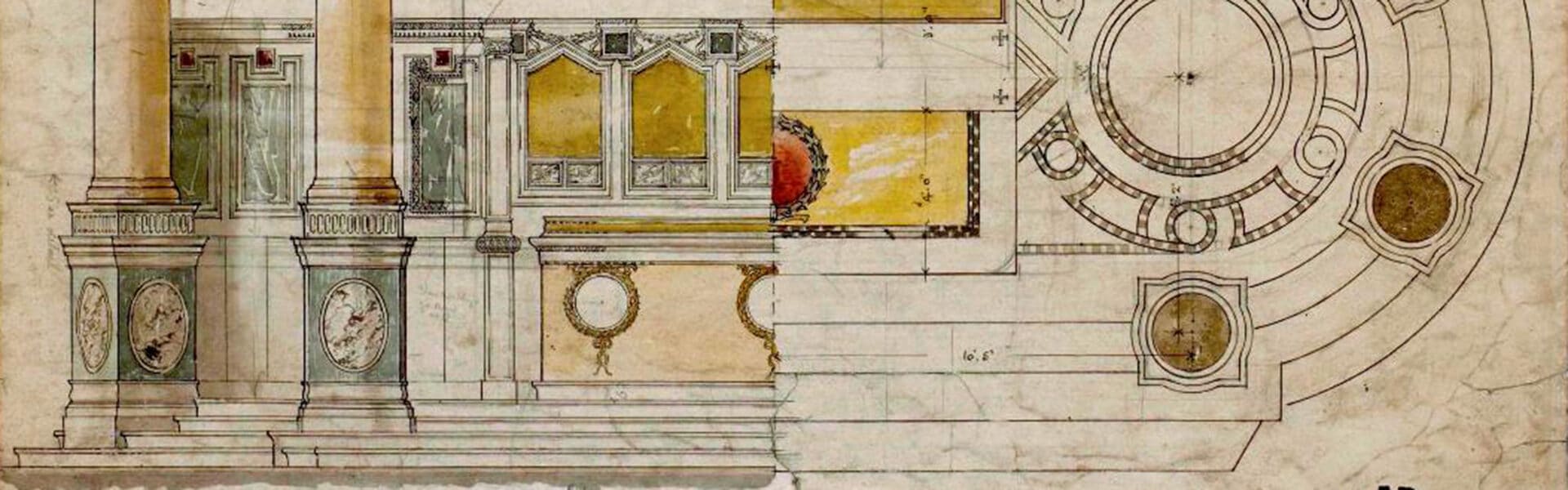

Bentley was convinced that Early Christian would not meet Vaughan’s requirements and he moved quickly towards his own version of Byzantine design intending ‘so far as I am able, to develop the first phase of Xtian architecture’. Cardinal Vaughan conceded defeat on his early design choice but refused Bentley’s original plan for two campanili, stating emphatically: ‘One would be enough for me.’

Westminster Cathedral reflects a unique and exciting combination of architectural influences with its massive Byzantine domes and wide interior space. The building’s location, right up against the street on Ambrosden Avenue, maximises the use of the site. The main advantage of the structure was that it could be built in brick (the candy-stripe design reference of red brick and Portland stone was taken from the existing mansion house flats in Ambrosden Avenue); it meant that the building could be constructed relatively quickly.

A formal design was finally approved in 1896, a year after the laying of the foundation stone. The domes and vaults were made of concrete, Bentley resisted the use of iron, and inspired by his Italian tour, he planned for the lower reaches of the building to be clad in marble with the upper reaches in mosaic. The solid foundation of the old prison was retained, providing a stable foundation for the building works. It also explains why, for a building of such stature, Westminster Cathedral has a relatively small crypt.

Sadly, the two men who had been so influential in the building of the Cathedral did not live to see its completion. Bentley died suddenly in 1902 and his Requiem was held at Clapham. He is buried at Mortlake. Cardinal Vaughan died the following year. The Cathedral was sufficiently completed to host his Requiem. His remains were buried at Mill Hill and finally returned to the Cathedral in 2005.

Further Reading:

- English Cathedrals: Andrew Sanders

- John Francis Bentley: Peter Howell

- Oremus: Westminster Cathedral Magazine: Patrick Rogers

- Catholic churches of London: Denis Evinson

- Westminster Cathedral and its Architect: Winefride De L’Hopital: Volumes 1 and 2

- Westminster Cathedral: Building of Faith by John Browne and Timothy Dean